Appreciate Where You Are, then Aim Higher

Discover Your Breakthrough Lifeline

If the unexamined life is not worth living, let’s intentionally find out what’s worth examining in our lives. The first approach can be to look back and appreciate how we got to this point. What are our achievements? What were the failures? What were the lessons? What are our lingering desires? Where do we go from here?

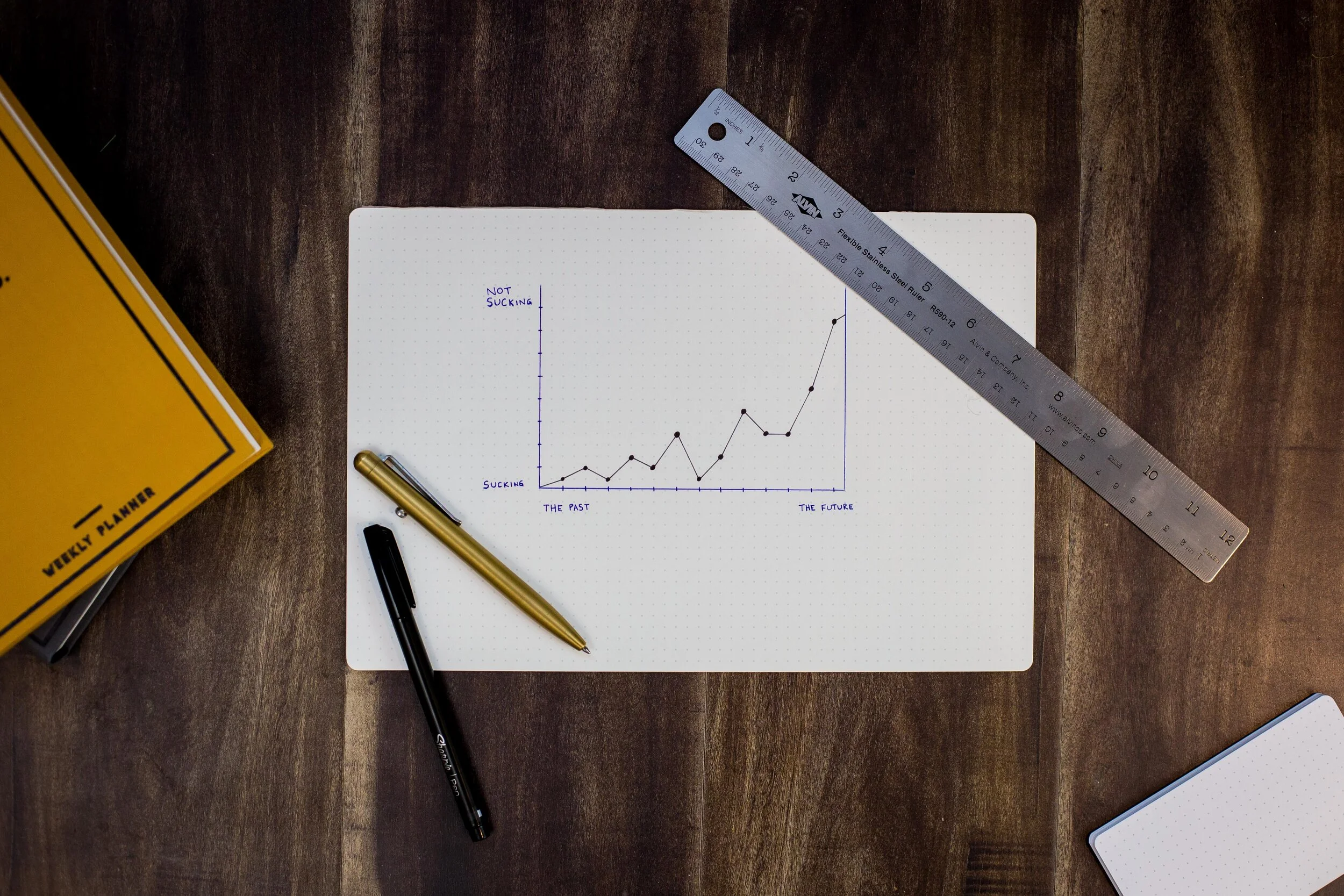

The Lifeline Exercise is a classic consulting tool that invites you to plot the six best and worst intervals in your life and analyze them through specific questions. After an initial approach, you can go deeper into detail and interpret the events that brought you to the present. Your Lifeline prompts you to interpret the lessons of the past to aim higher, to seek Breakthrough and conquer meaninfgul goals.

In this Chapter, I’ve used the analysis of my own Breakthrough Lifeline to guide you in your own exploration. You can find the description and instructions below.

CHAPTER INDEX

The Lifeline Exercise - Description

What you need:

A blank piece of paper

A pen and color markers or pencils

Between 30 to 60 minutes of uninterrupted time

Example of a Breakthrough Lifeline (Attorney)

Instructions:

Write down and Rank the six (6) best intervals of your life, both in performance and satisfaction.

Write down and Rank the six (6) worst intervals of your life, both in performance and satisfaction.

Plot your lifeline: Plot your lifeline as in the diagram above by locating the approximate position of each positive and negative event in your life between your Birth and Now (your current age). Positive events go above the line and negative events go below. Label each event with your age at the time and your (+) or (-) rating. Connect the points above and below the zero (0) line sequentially (chronologically).

Now, answer these questions:

LOOK AT THE POSITIVE TIMES: What kind of benefits did you produce for yourself during these times?

LOOK AT THE NEGATIVE TIMES: What did you learn about yourself from these experiences?

Look at the shape of your Lifeline:

How high are the high points? How low are the low points? What is the time interval between the high points and the low points? What does the general shape of your lifeline suggest to you (is it jagged, flat, undulating, climbing or descending?) What were the Breakthrough moments? How does it inspire your future?

What are you most proud about when you look at your Lifeline?

Make a list of the Top-10 things you are most proud about and rank them according to your feelings.

What does our Lifeline say about your Purpose in life?

Looking at your Lifeline, finish this sentence: “I’m in this world to…”

Your Lifeline - The Deeper Dive

Here are two suggestions to analyze your Lifeline in detail:

THE DEEPER DIVE: In the chart below (Example of a Deeper Dive), I show you how you can use a spreadsheet program or charting paper to plot your entire Lifeline in key segments and find a deeper interpretation of the initial exercise. The example is my own Lifeline from my birth to the Present. Within this Chapter, I’ve expanded my personal Lifeline Exploration to tell my life’s story divided in periods of growth. A Lifeline segment precedes each period or stage. You can work on your Deeper Dive in a similar way.

THE HERO’S JOURNEY meets the 4i STAGES: You can go even deeper in your analysis of your Lifeline by exploring how your Lifeline matches three of the The Hero’s Journey phases (Call to Adventure, Quest and Death/Resurrection), as well as the 4i Stages of seeing The Glass Full and a Half (Imagine, Improve, Inspire and Ignite).

Watch a short TEDEd video on “The Hero’s Journey” and its stages:

Here is the graph of my exploration of my Lifeline below on MS Excel (I’ve divided my Lifeline in major Time Periods separated by major decisions I took):

My Lifeline - Example of my Deeper Dive

my lifeline exercise - example of how you can chart your life in significant periods using a spreadsheet program

Imagine

1) ARGENTINA 1958 - 1985: Tried to conform, witnessed a massacre and dreamed of emigrating to change my life

Call to Adventure: Witness of the massacre at St. Patrick’s Church. Paid for my trip to Europe and the U.S.

Quest: Study Medicine and teach tennis professionally. Discover my passion for sports with Enrique Pisani.

Death and Resurrection: Quit Medicine and Emigrated to the U.S.

Improve

2) USA 1985 - 1993: Entrepreneurial projects to reside in the U.S., success in sport psychology, move to the UK

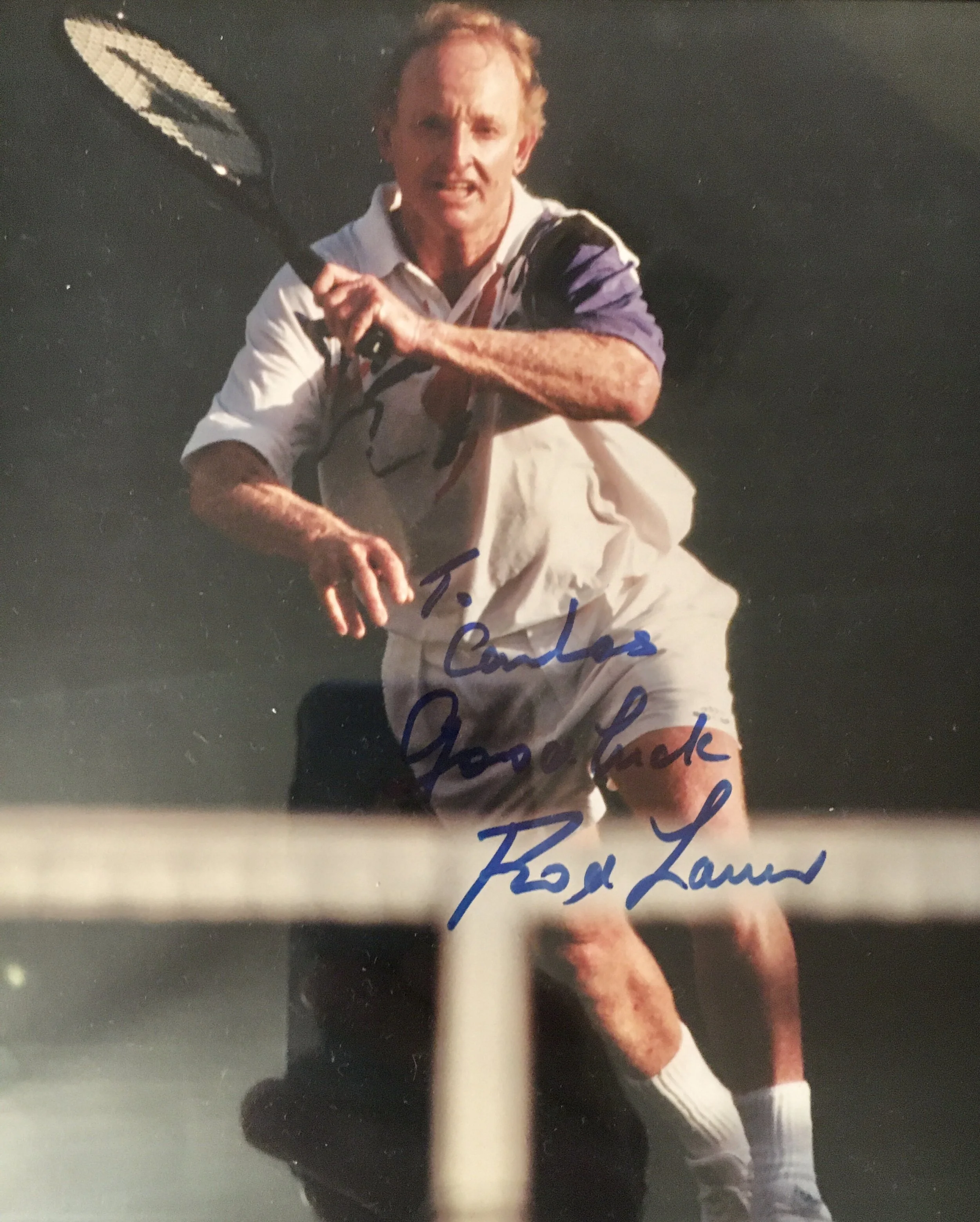

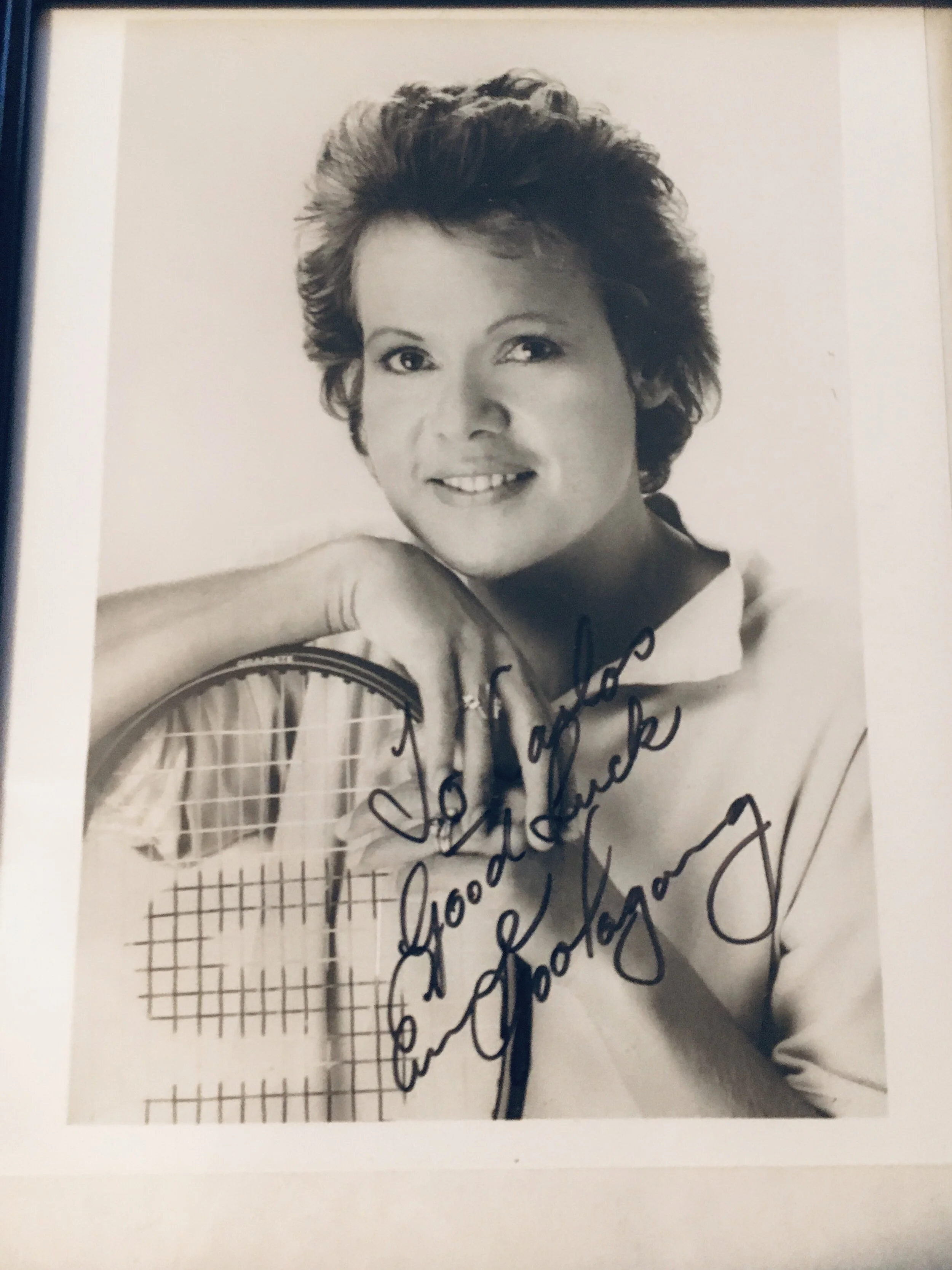

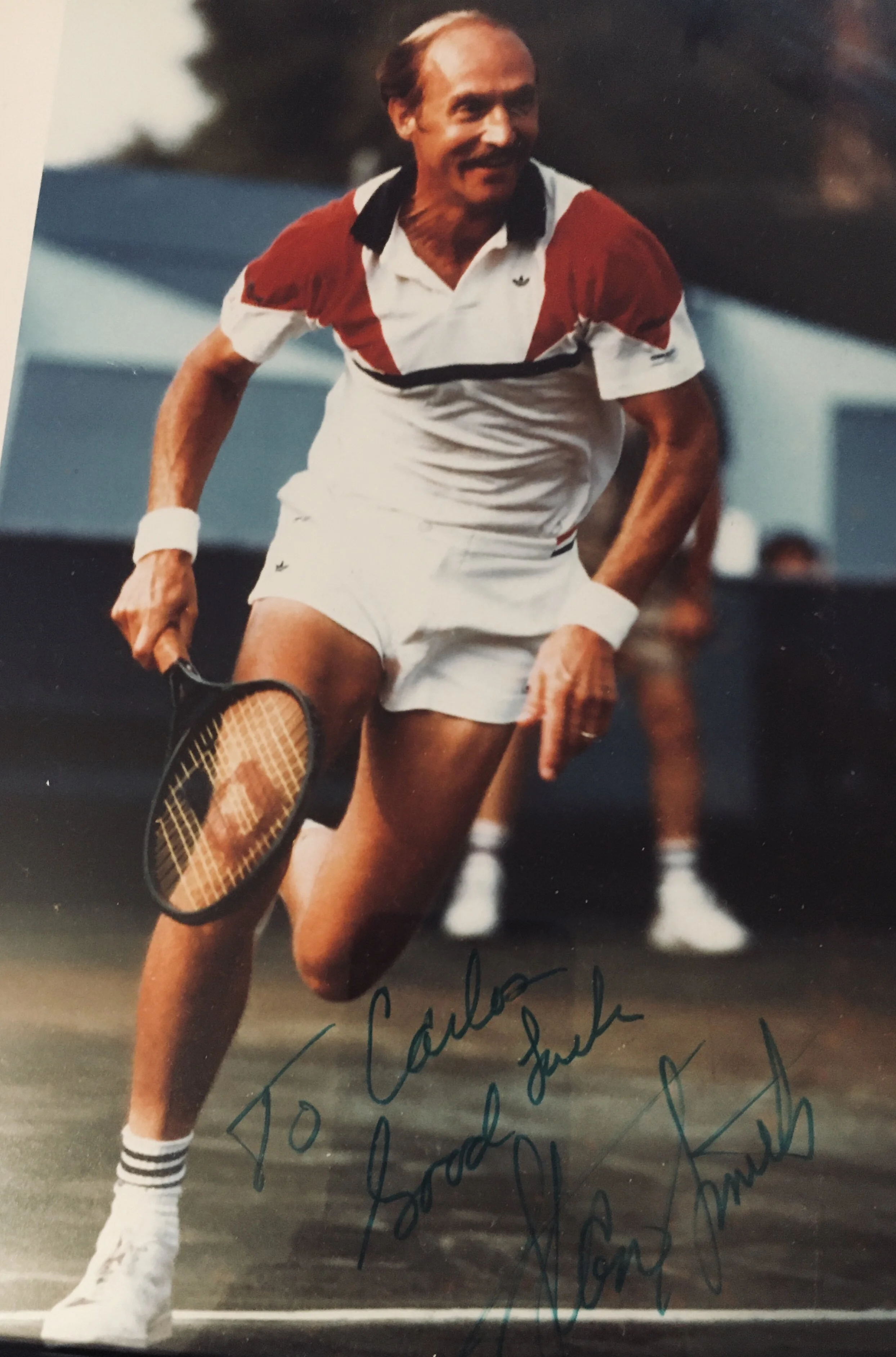

Call to adventure: Teach with Van der Meer in the U.S. and Europe. Organize the Dr. Jim Loehr European Tour

The Quest: Expand Dr. Loehr’s business internationally; help tennis players win Grand Slams. Write a play

Death and Resurrection: Leave Florida, create my own company and move to England to run my first project

Inspire

3) ENGLAND/USA 1993 - 2000: Develop UK project, return to U.S. to join Internet start-ups. Move to Houston

Call to Adventure: Working in England, writing my play to produce it in 1996-97. Moving to Houston

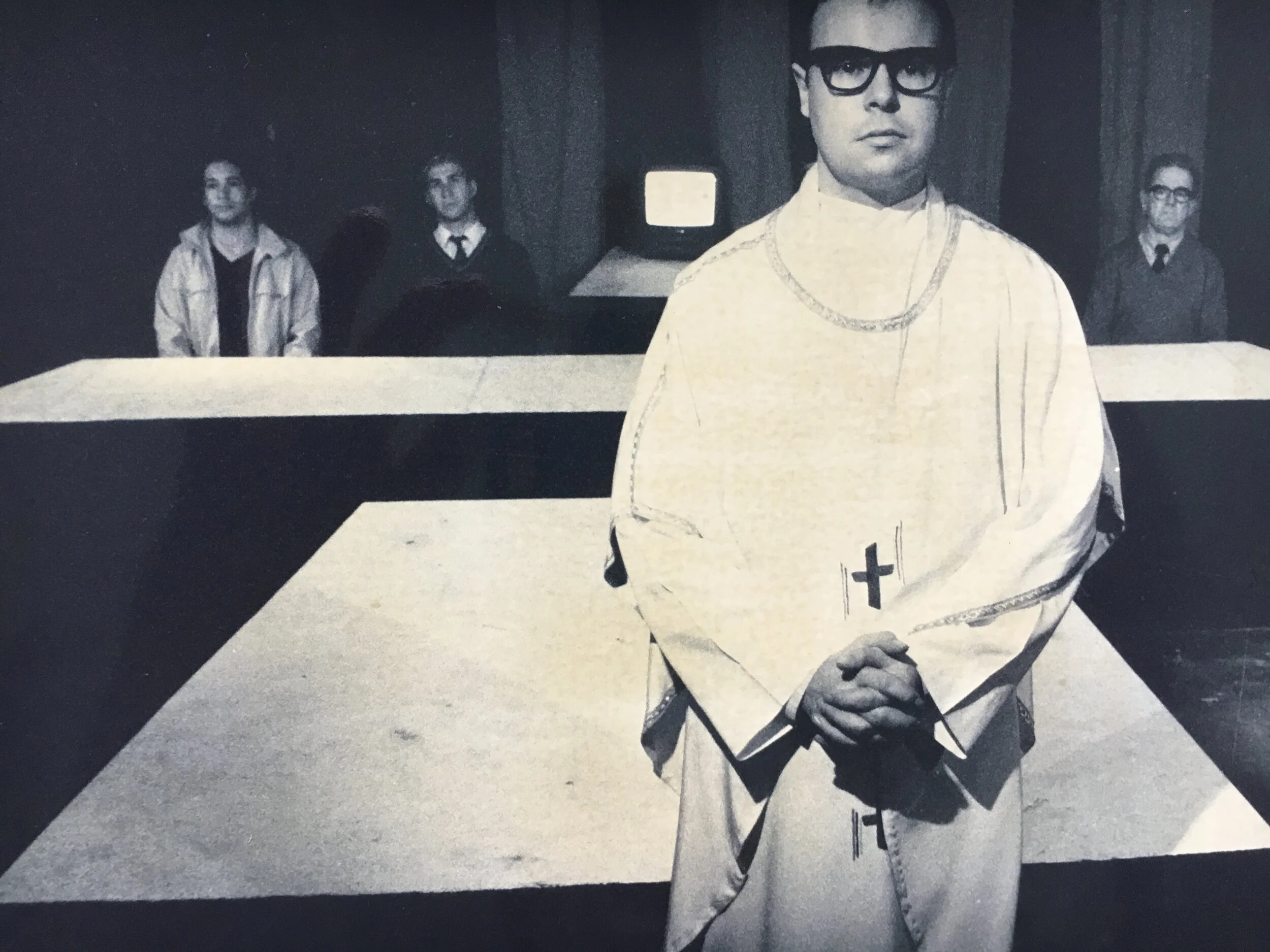

The Quest: Producing my stage play in Tampa, Buenos Aires and London, as well as a TV Documentary

Death and Resurrection: Leave Houston, move to Charlotte and work in Switzerland in 2000

4) SWITZERLAND 2000 - 2017: Working in Switzerland in Swiss Private Banking projects

Call to Adventure: Leverage my Coaching and Theatre experience to inspire and motivate clients

The Quest: To work with my friend Gustavo Raitzin to support his strategies and teams for success

Death and Resurrection: Gustavo Raitzin retires, I focus on U.S. entrepreneurial projects and sports

Ignite

5) USA 2017 - PRESENT: Seeking a bigger platform to inspire others and ignite Breakthrough opportunities

Call to Adventure: Leveraging coaching into Motorsports, Fittipaldi Championships and leAD Sports Tech

The Quest: Producing inspirational sports films, mentor at leAD Sports Tech and producing my screenplay

Death and Resurrection: (Not there yet… but focusing on having a larger stage to inspire more people)

TOP-10 THINGS I’M PROUD ABOUT (1958 to PRESENT):

I think it’s important to select the Top-10 points of pride in your personal history. Not all events feel the same, even if we’ve ranked them high in our Lifeline exploration. Some of them reveal “the inciting incident” that motivated us to start something or change direction. Others reveal “the secret motive” driving something we do. A few deserve a mention because they required great effort, sacrifice and they were triggers for our personal transformation. Here are my Top-10 points of pride in order of feeling, not in chronological order:

Writing and producing a play and a TV documentary in 1996-97

Becoming a US Citizen in 1999 having married Karen and getting a sense of belonging

Writing a book and writing a screenplay

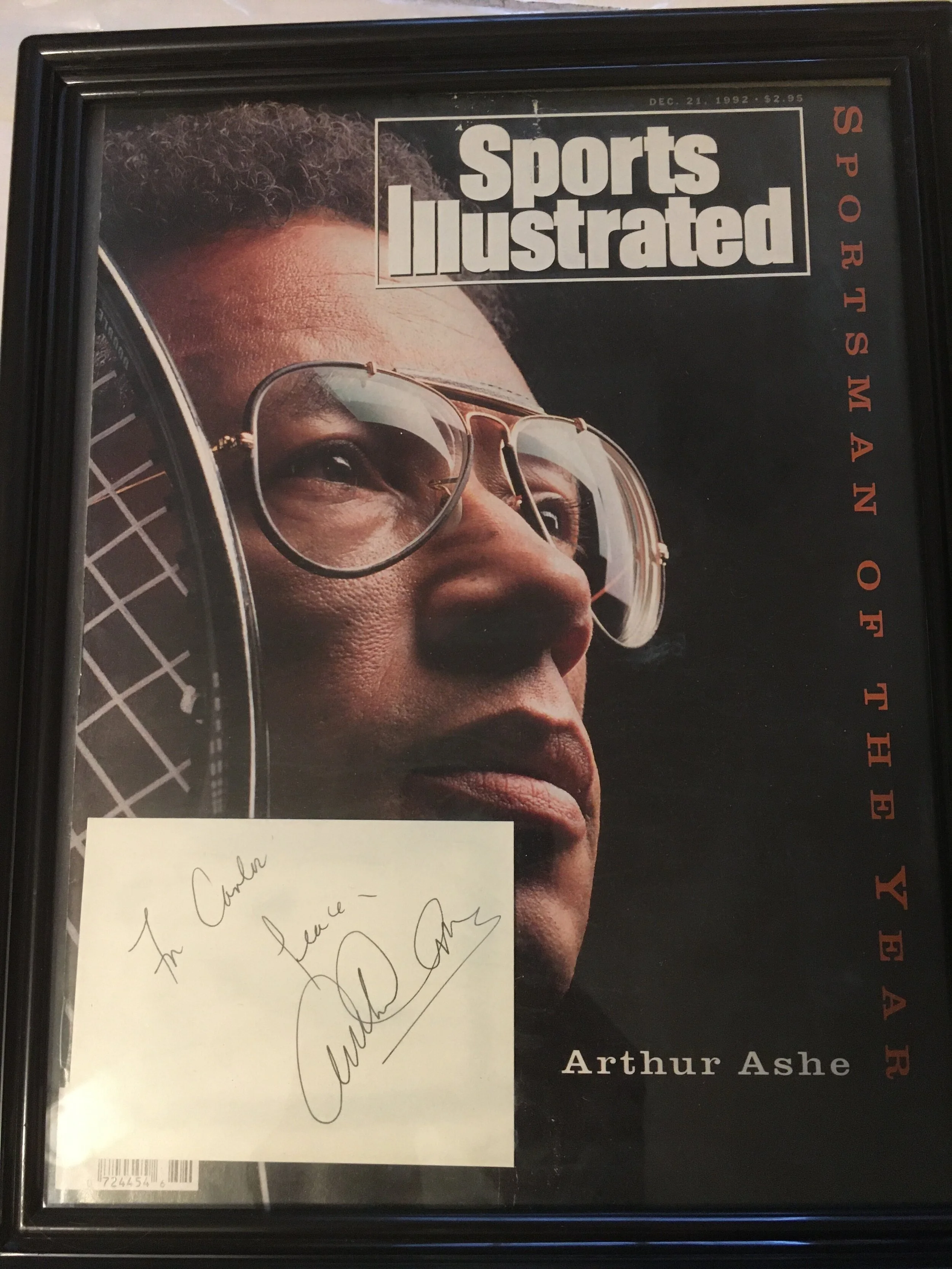

Helping Gabriela Sabatini, Sergi Bruguera, Pietro and Enzo Fittipaldi win major international Championships in their sports

Buying a house in Charlotte, NC in 2003 and finally call a place “home”

Winning tennis tournaments when I was 17 with my father watching the finals

Working with my best friend in Switzerland in change management from 2000 to 2017

Learning with Richard Saul Wurman, Dr. Edward de Bono, Dudley Lynch and other mentors

Working with Dennis Van der Meer internationally and organizing Dr. Jim Loehr’s Speaking tours in Europe and Japan in 1989-1992

Winning the Amancay Literary Prize in 6th grade

My Life’s Story - according to My Lifeline

IMAGINE - Stage 1 - Argentina (1958 - 1985)

Thinking is My Inheritance

I grew up in Argentina in a family of high achievers who taught me that a skillful thinker is one that can always improve, someone who is competent but not arrogant nor defensive, a confident individual that evaluates alternatives and differing viewpoints before making decisions.

In the early 1900's, my Lebanese and French grandparents overcame monumental obstacles in Buenos Aires to give their children access to higher education. The Salum and Brieux sons and daughters honored them by becoming scientists, lawyers, engineers and business managers who made significant contributions and gained international recognition. When I look at my family, what stands out is the quality of their thinking: Optimistic, Entrepreneurial, Determined, Resilient, Socially Conscious and Universalist. They aspired to contribute to the whole of Humanity.

THE SALUM FAMILY

YAMIL, MARIA LUISA, JOSE, SOFIA AND ODETTE SALUM

My paternal grandparents had left behind their families in Lebanon located 7,600 miles away, never to see them again. They were getting away from scarcity and pandemics, and moving towards the promise of a new start in America.

Jose (Yousef) Salum, my grandfather, left his town of Ghosta (above Beirut) around 1910 by ship and arrived in Buenos Aires without money, documents or language skills. He was only 15 years old and just had a piece of paper with the name and the address of a Lebanese family who hosted him for a while. He managed to get jobs and become an entrepreneur. He never wanted to work for someone else and he succeeded at remaining independent all of his life.

Sofia Khoury El-Barri, my grandmother, was a teenager when she left Lebanon by ship with New York City as her destination. Ellis Island was closed due to a pandemic and the only port accepting immigrants was Buenos Aires. Considering their situation and the possible delays, her chaperons agreed to extend their trip and travel South, hoping to be reunited with their U.S. family later. It never happened. She was often homesick and her Argentine hosts thought that she should be married to feel grounded.

Jose and Sofia met in Buenos Aires thanks to the matchmaking efforts of their Lebanese circle of friends. They both had survived the long boat trip to America in search of wonder and abundance. He was older, serious and business-minded. She was bubbly, kind and gregarious. Both were Catholic Maronites, which connected them with local networks through their church. They both had strong accents in Spanish, yet their kindness, polished manners, entrepreneurial ethic and positive attitude endeared them to people. They were not unique; it was a time of strong immigration currents towards South America.

My grandfather established bazaar shops and soon prospered as a retailer of housewares. As immigrant minorities, some of the Lebanese and Jewish in Buenos Aires learned to cooperate and congregated in specific neighborhoods to defend their trades from the economic influence and prejudices of others. I found out about this historical fact from published research and direct testimony of Jewish families who had done business with my grandfather and had fond memories of him. It made a difference in my upbringing. I’ve been welcome by Jewish friends and clients all my life and their viewpoints, trust and wisdom have enriched me immensely.

Jose and Sofia had three children, a boy and two girls, close together in ages: Yamil, Odette and Maria Luisa.

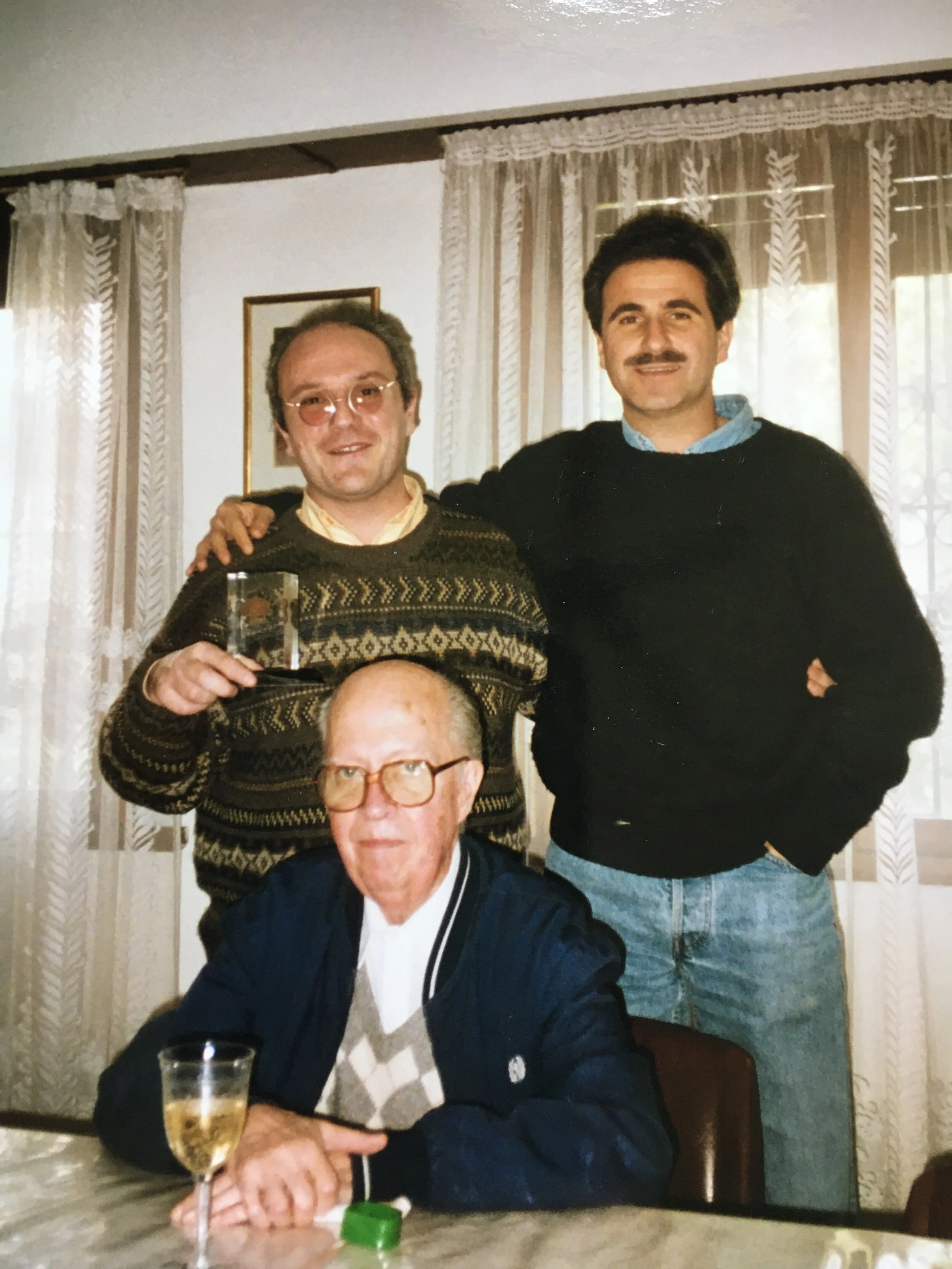

dr. yamil salum, my father

Yamil, my father, was born in 1922 and became a good student. When I saw some of his notebooks for the first time, I was amazed at the impeccable calligraphy, the tidiness and the intricate diagrams he had to draw with Chinese ink and dip pens with metal nibs. He liked science and attended the Otto Krause technical school, from where he went to the National University and earned a PhD. in Chemistry - the first in the Lebanese lineage to have one. His early work focused on insulin production at the prestigious Instituto Malbran, followed by a position at Eli Lilly Laboratories. Argentina would have two Nobel Laureates who advanced the research on insulin, which benefited diabetes sufferers worldwide.

His career progressed at U.S. pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies (Sydney Ross, Winthrop and Schering Plough). His final position was with Copetro, a division Great Lakes Carbon, with whom he set up an automated calcium petroleum coke distribution plant, essential for aluminum production for the automotive industry. He had roles related to Quality Control. Through his career, he contributed to the Argentine Chemical Society, which honored him for his lifetime achievements and his promotion of science and industry. He passed away on his 93rd birthday in 2015.

my aunts odette and maria luisa salum

My two aunts, Odette and Maria Luisa, were steered towards non-academic options and excelled at what they chose to do. Odette became one of the first occupational therapists for the disabled in the country, trained by British nurses (one of them was the sister of film director John Schlesinger's, Academy Award Winner with “Midnight Cowboy” - with whom she had great rapport). I visited the Institute, which was staffed with top-level medical experts, and saw a model operation were helping their patients become autonomous was paramount. Odette felt rewarded every time a disabled individual would find employment and could fend for himself or herself in society. Maria Luisa had strong management skills and joined Asicurazioni Generali, the renowned Italian insurance company with its headquarters in Trieste, and climbed up the ranks to become the director's chief of staff. When he retired, she stayed a few years longer and helped navigate the transition to a new team.

My aunts never married and lived together in nicely decorated apartments that we always wanted to visit to have long conversations over tea and outstanding sweets with them. They remained curious, informed and engaged throughout the country’s constant political turmoil. I admire their capacity to forecast, save and invest to shield themselves from the rapacity and ineptitude of Argentine governments. They were a source of love and guidance for my brother and me when we most needed it, especially during the oppressive dictatorships and before we emigrated, when our safety and clear decision-making were crucial to our future.

chloe, estela and robbie salum

My brother Robert (Robbie) is a year and three months younger than me. He’s blond with blue eyes, while I originally had brown hair and hazel eyes. Robbie is calmer than I am, a keen observer and judge of character. He’s a tennis coach in Sarasota, Florida and he's married to Estela Madrazo (an architect and Spanish teacher) and has a multi-talented daughter, Chloe, a university student with a passion for arts and science.

Robbie and I share a love for the absurd and surreal humor, which we exercise daily when we talk with my mother online. He’s an excellent gourmet cook, preparing several challenging and complex dishes every day as a way to relax. Their description alone makes me laugh for how impossible they seem for a normal person. Robbie is also a connoisseur of men’s fashion, a sommelier and has a large collection of recorded music. Like my mother, he paints very well and is a highly imaginative artisan.

We always lived in apartment buildings in a Buenos Aires’ suburb called Belgrano, where you still find some of the original homes built by British families who mostly worked for the southern railroad and shipping companies. We grew up playing together at home while my mother was at work. It seems we were not kind to nannies, which I would blame it on separation anxiety. Later, we played soccer with neighbors on the nearby square, rode our bikes and participated in all kinds of mischief. Some of those incidents still make us laugh hard; we were creative even for disaster. To keep us off the street, my parents made a big financial effort and bought a membership at a British club two blocks away, where we learned tennis starting at 9 years old and developed most of our social life.

Tennis changed everything for us. Initially, we had to endure the scorn of the British adults for newcomers and understand their codes of conduct. We also had a couple of fights with entitled kids who saw we behaved and dressed differently (we knew nothing about clothing brands as status symbols). It didn’t help that we didn’t play rugby either. Within a few years, we had a complete tennis game, so we started playing with adults, which gave us more court time and recognition.

Being so close to the club, we could train often and spend the summers at the pool. Robbie always played with more ease than me, became a competitive swimmer and a cricket player as well. I was single-minded about tennis. As my doubles partner, he had a reassuring influence, as he had better emotional control and execution under pressure. I had to work hard at it, always.

When he was 16, Robbie decided to train at Club San Fernando, my parent’s first club where they kept a membership. It was an hour away from the city, ideal for a weekend getaways, barbecues and rowing. Their tennis school had produced several extraordinary talents who held world rankings, including the Gattiker brothers (national champions) and Jose Luis Clerc, who would become #4 in the ATP and play legendary Davis Cup matches with Guillermo Vilas, the trailblazing national hero. During this time with them, Robbie grew tremendously as a player and joined the best teams in interclub competitions.

Robbie studied Economics and started teaching tennis with me to stay connected to the sport. He dropped out close to the time I quit Medicine, as we saw most professions deteriorate due to the neverending economic crisis. We focused on building a tennis services company (Tenislab) and found managing pros and club staff quite a nightmare. My father’s management support helped us stay afloat. After I left Argentina, Robbie run a large tennis club and spearheaded the birth of paddle tennis in Argentina. He got married and divorced within a year. Shortly after, he met Estela through friends and later they got married in Sarasota in 1990, while we were working with Dr. Jim Loehr. She has two married brothers (Daniel and Fernando), both entrepreneurs, two nephews and two nieces in Buenos Aires. In 1990, Robbie and Estela joined me in the United States and benefited from a fast-tracked visa process that gave us all peace of mind.

THE BRIEUX FAMILY

standing: olga, guillermo, eduardo, jorge and sonia with their parents marta and fernan brieux.

My maternal grandfather's family came from Bordeaux, France, attracted by the opportunity to succeed as builders of railroad ties, roads and bridges in northern Argentina. The breadwinners fell ill and my grandfather, Fernan Brieux, had to work from an early age to support his relatives, especially the women. He was the youngest of thirteen children and did not have access to higher education. Through sheer effort and dedication, he became a senior executive at the National Power Company (CADE) and married Marta Clement, my grandmother.

Fernan and Marta had five children: George, Sonia (my mother, born in 1926), Olga, Eduardo and Guillermo. After he built a house he designed, my grandfather decided that all his five children would study and get a university degree, so they would not have to struggle like him. Financial stability, academic success, self-reliance and significant contributions to society would be his legacy to them.

Dr. George Brieux, the first-born, was a Doctor in Chemistry who complete a post-graduate degree at Leeds University in England and was influential in the Argentine chemical industry as a university professor, a researcher and as president of the British Council. Queen Elizabeth awarded George an OBE title (Outside British Empire) for his contribution to the United Kingdom's brain trust after securing scholarships for two prominent talents: Dr. Cesar Milstein, 1984 Nobel Prize Laureate in Medicine and world-renowned classic music ensemble Camerata Bariloche's founder Alberto Lisy. Late in life, he married Dr. Adela Amico, a Chemistry professor, who lived until 104 years of age, autonomous and disciplined, in her beautiful apartment in the city center. She was always well informed and lucid. Bank employees asked her for pictures together when they read her age in her documents.

One of his most interesting projects George worked on was how to improve the taste of yerba mate, the national green tea drink. During my trip to Paris in 1981, he asked me to find the legendary and rare book “The Physiology of Taste,” by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, published in 1825 and revered by chefs worldwide. I found it at an antique bookstore in St. Germain and he was impressed by my detective work.

Uncle George introduced the kids in our family to the adventures of Tintin (in French, English and Spanish). He traveled often and would bring back his books to entice us to learn languages. He had eclectic interests and was attracted to the extraordinary. I was completely fascinated with Uncle George’s stories about the world cities he had visited. Despite the subjacent prejudices of Hergè, its Belgian author, Tintin the reporter invited us to imagine new experiences, learn about the world and to be a contribution, never mind the madness and absurdity around us (we had plenty of both in Argentina). I saw Tintin as a creative, proactive thinker and a reliable friend with a sense of justice. Tintin ignited my desire to travel around the world and be like Uncle George, to become a storyteller that could excite people's imaginations and encourage them to venture out and discover by themselves. As in his beautifully illustrated books, sometimes you choose the adventure, often times it chooses you. You need to decide if and why you will embark on it.

My grandfather Fernan Brieux was a free thinker and a visionary. I remember him as a man with gravitas and firm in his convictions. He read profusely about a variety of topics, which made for richer conversations at a time that there was no television to obstruct pure dialogue. Although in those times women would spend their lives as homemakers, he foresaw that Argentina would one day legalize divorce despite its strong Catholic base. He wanted his two daughters to study and be able to sustain themselves financially. My mother's true vocation was to be a painter, but my grandfather persuaded her to study "something that would make money" - therefore her PhD in Chemistry.

my mother at the pasteur institute in paris, france

Sonia and Olga were among the first women to obtain Science degrees in Argentina. My mother met my father through Olga at the university. She earned a scholarship at the prestigious Pasteur Institute in Paris, where she spent a year doing research, and another with Pitman-Moore laboratories in Indiana. She returned to Buenos Aires to marry my father and take a leadership role as a research scientist at the National Academy of Medicine, where she studied the genetic origins of leukemia and hemophilia for three decades. To get married, she agreed to a Catholic baptism, although she always maintained a healthy philosophical distance from strict religiosity.

My mother thinks and operates as a CEO with focus, determination, resiliency and the ability to persuade others to join an epic vision. She balanced her role of wife, mother and professional masterfully, never sacrificing one for the other, and transmitted her sense of being "a citizen of the world who creates possibilities" to my brother Robert and I. As feminism was gaining ground, I remember journalists from women’s magazines interviewing her. She achieved international recognition and renowned writer Victoria Ocampo funded her work in part, clearing a path for future female scientists to break through and succeed. Some of them worked in my mother’s team.

[Image Gallery: When she retired, my mother fulfilled her childhood dream of becoming a painter, successfully exhibiting and selling her abstract work to corporate and private collectors.]

My mother’s example has made a strong imprint in me. As a leadership performance and breakthrough thinking advisor, I enjoy helping women leaders as brilliant and determined as my mother and, in her honor, I always share one fundamental suggestion: "Stake your claim, define your uniqueness and insist on how you are a powerful contribution." My mother has always demonstrated her talent, making an impact as a thinker, a citizen, a scientist and an artist. The women in our family see her as a beacon when they must make crucial decisions.

my aunt olga and my uncle humberto mandirola in paris, france

My aunt Olga became a physicist specialized in quantum physics and a university professor. She married engineer Humberto Mandirola and had three children: Fernan, Pablo and Marta. Olga was a trailblazer with a unique intellect and straightforward personality. Humberto participated in the design of the Buenos Aires University Campus, featuring modern buildings and sports facilities, which became a benchmark for future undertakings. Their lives centered on academia and intellectual pursuits, as well as traveling. My cousin Fernan studied Medicine, specializing in ICU and Emergencies - and simultaneously developing an international software company providing solutions for hospitals. My cousin Pablo is a lawyer who immigrated to Barcelona and assists Latin American companies establish offices in Spain. He married two times and has two children, Celia y Guido. Marta studied pedagogy, became an artist and married Horacio Socolovsky, with whom he has four adult children: Matias, Julian, Lucas and Marina.

Uncle Eduardo was an attorney, calm and measured, a voracious reader, researcher and a blog writer under the pseudonym Jovialiste. He published several works, one of them an interesting book on the mechanisms of humor. He expanded the research of the genealogical tree of the family. He married Amelia Olivera, also an attorney, and mother of their two children: Enrique (deceased) and Carolina (a psychologist), who is married with two children.

Uncle Guillermo was a land surveyor and traveled through Argentina extensively. He was a bachelor with a quick sense of humor and a passion for gourmet cooking. Compared to the urban lifestyle of his brothers and sisters, he experienced the “gaucho” customs to the fullest during his extensive traveling through the provinces.

[Image: My father took this picture of my first encounter with an elephant alongside my mother. I choose it as my first memory of being in awe]

Since an early age, I was in awe of my family's hunger for information, knowledge, conversation, cultural engagement and travel. Their desire to better themselves and excel at their professions was palpable and it became part of my identity.

one of my mother’s watercolors, from her last explorations as a painter

My parents gave me the gift of the values they lived intentionally and the activities they appreciated: family, education, the arts, creativity, kindness, ambassadorship and tennis as an international language. Learning from them by example was exciting, and made the effort of studying more engaging; it gave it purpose. I understood the "Why."

Their courageous commitment to being fully alive rather than to "making a living" influenced me deeply. I chose to pursue breakthrough experiences rather than sticking to a career, letting awe be my compass.

While more analytical individuals might consider my idealism a serious character flaw, it has actually given me amazing opportunities to prove my value beyond expectations.

While many of my friends sought certainty, I always comfortable with desire. I was focused on the future, on what could be, on how something could be better - despite the overwhelming odds against it. Corrupt and inept Argentine politicians and a fractured society would provide monumental obstacles during the first 25 years of my life but strengthen my resolve to live elsewhere.

I'm proud to have inherited my ancestors' thirst for intellectual freedom and individual progress, along with their rejection of authoritarian rule (the Brieux ex-libris designed by my grandfather Fernan reads: "ny roi ni archevêque," neither king nor archbishop - Plumeau and Masse are last names). Education and fruitful effort were the conduits to understanding, represented by method, order and perseverance.

Tragically, the dictatorships that ruled Argentina from 1966 to 1983 denied my generation the chance develop as free thinkers in full. The National Security Doctrine, implemented by the U.S. government in alliance with South American military regimes, engendered "Operation Condor," a vast international plan to install a free-market economy through shock therapy, widespread privatization and record levels of external debt.

Operation Condor involved targeted abductions, disappearances, interrogations, torture, and transfers of persons across borders. According to a declassified 1976 FBI report, it had three levels. The first was cooperation among military intelligence services. The second, to detain and disappear dissidents across borders. The third and most secret phase, was the creation of special teams of assassins to operate anywhere in the world and kill political leaders who could incite opposition to the military states.

MY CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

kindergarden - with sister mercedes

At 4 years old, Robbie and I went to a kindergarden run by Catholic nuns located near our tennis club. We both loved Sister Mercedes, the youngest of our teachers. We learned to read and write and play with kids whose names I remember to this day, especially Robin and Gerdt, two German brothers, our first international friends. I also remember having my first crushes on girls, being in a costume for the first time and not being comfortable with obligatory prayers to the Virgin Mary, as I could not figure out why we gathered to talk to a statue reciting words that made no sense.

When I was six, my first day in school was an eventful one. My parents had chosen Colegio Manuel Belgrano run by Catholic French Brothers, a branch of the Brother Champagnat education model: strong on academic information and sports, reasonable on discipline and a pipeline for leadership development. We spent the morning sharing our names and writing the letters of the alphabet on the blackboard. I already knew how to read and write, so I paid attention to my peers’ personalities: who was confident, who was shy and who seemed lost facing the class up at the blackboard.

At lunchtime, I was supposed to eat at the school and have lessons until 4:00 pm, when a private bus would take me home. I decided the morning had been boring and since I knew my grandmother Sofia lived five blocks away, I took off on foot and didn’t tell a soul. While waiting to cross a major avenue, I saw my grandfather Jose going in the same direction. I stood beside him and said hello. He was shocked and asked me where I was going. “To your house, for lunch,” I said. He smiled, shook his head, took my hand and we walked together for two blocks. Mayhem ensued, as my father drove hurriedly from work, alerted my mother at her laboratory and called the school to find out how nobody noticed I had left. Meanwhile, I had sandwiches with my sweet grandmother, who seemed both amused and confused. I answered the adults’ questions nonchalantly, which baffled them even more.

I’m certain my actions that day hold the clues of many of my decisions in life afterwards. The next morning, the young religious brother (Ricardo) was not too happy to see me and kept a close eye on me, escorting me to the lunch hall at noon.

The French Brothers taught a strong Humanities curriculum, so I did pretty well year after year, except for recognizing I had a strong distaste for the rigors of math, where I found the emphasis on the right-or-wrong answers irritating. My sense of the world was more nebulous and fluid than black-or-white: blue and grey are fine; shades of grey are interesting. Daydreaming, reading, writing, drawing and playing soccer and tennis were my chosen gates to nirvana (I didn't have a TV till I was fourteen). I read for pleasure and loved to let my imagination fly, especially having climbed a tree.

Our music teacher was a peculiar character with a keen understanding of his role as “emotional manager.” He knew that music was an outlet for our high-pressure education, yet he intended for us to learn to sing anthems, to understand classic music and to be able to analyze the music we liked. I clearly remember the day he taught us about Miles Davies and Bill Evans, and described the intricacies of modal jazz. He called it “the antimatter of music” and I was hooked, I wanted to know more. I’ve never been able to understand music fully, but I can superficially analyze a composition’s structure thanks to him. Two decades later, when I listened to “Flamenco Sketches” in “Kind of Blue,” I had a religious experience. It all came back to me; I had a memory trigger. That was the beginning of my jazz collection, mostly of pianist Bill Evans, who has transformed my understanding of beauty, truth and the purpose of art. “I want to communicate a qualitative thing, what I consider to be above the ordinary, outside of ordinary experience (...) It has to do with a sense of beauty, but I think once somebody perceives a thing like that, it can change their lives, so that you can say ‘there’s something real, and I might as well live with that." [Bill Evans]

i’m the goalie, saving the day against our eternal rivals, the “b” division

We played soccer at school (making the team was a status symbol) and I became a decent #10 until I was 12, when the body blows started to get harder. I had tried rugby due to peer pressure and found it immensely boring (I would never get the ball and there was senseless punching, for show, and rarely penalized. I liked my teeth just where they belonged). By then, superstar goalie Hugo Gatti had moved into our building and talked with us when he was between matches with Club River Plate and the national team. I was star struck and formed the “Hugo Gatti Fan Club,” of which I was the only member. Inspired by his tales and after reading the sports magazine “El Grafico” weekly, I decided to become a goalie myself and enjoyed the individual attention until the body blows got worse.

Tennis seemed a logical alternative: I could hit the ball all the time, winning was up to me and if I played well, I would get the attention I deserved. There was quite an obsessive attention to elegance at our club, with mandatory white attire and brands such as Fred Perry and Lacoste in vogue. I had neither, but I aspired to earn them. Our club had plenty of snobbish players with shabby strokes, and we kids thought they were clowns.

There were always new books and records at our house. My parents and relatives had grown up accustomed to saving a portion of their salaries to buy them monthly, it was a tradition. Through their encouragement, I gradually experienced the sublime through artists such as Johann Sebastian Bach, Joaquin Rodrigo, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Francis Bacon, the Bauhaus, Bill Evans, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius de Moraes, Tamba Trio, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dickens, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Julio Cortazar, Mario Vargas Llosa, Pablo Neruda, Alejo Carpentier, Harold Pinter, Samuel Beckett, Alberto Giacometti, Carlos Alonso, Quinquela Martin, Guillermo Roux, Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Philip Glass and other masters. Quite an eclectic selection that left an indelible mark in my subconscious.

winner of the premio amancay - my school’s literary prize

My school had established a literary competition for sixth grade students called Amancay Prize. The goal was to write a composition about the national flag. I chose the title “High Up in the Sky,” the same one as the flag’s song we sang at patriotic celebrations. The date was November 6, 1970 and my winning submission read as follows:

“It’s been many years since I see it, my National Flag. Day after day, it raises up the mast in front of the students in a reverent ceremony, deserving of the most respectful silence and patriotic pride. Such ceremony is possible because, as the nation’s patriots do, the students fight every day against ignorance, the scourge of Humanity. There is no better homage for the nation’s symbol that to begin with hearts inflamed by martial music, the ascending cloth and the national shield fixed, vigilant. Two heroes flank the flag: Belgrano and San Martin. They benefited the nation and their effort made possible for the flag to fly today. When their illustrious lives ended, others continued their work and it is now our time, it is our generation’s duty to continue carrying with a firm pulse the standard that represents the country and its struggle. When it rains, the flag is not there; then we must demonstrate that we carry it in our hearts, that without its material presence we reflect its glow. Honoring the flag also implies being patriotic but without fanaticism outside our borders. There are those who understand the flag by its dogma, by its symbolic essence, by what it represents. As I prepare to enter High School, where I will be able to understand you better, my flag, I just wanted to give testimony of how I feel as an Argentine.” - Carlos Marcelo Salum Brieux

Encouraged by the prize, I wrote poetry and short plays profusely after that (very few decent ones, I kept just one). Many years would go by until I would confidently call myself a writer again.

I was often chosen as one of the leaders in my class, elected by my peers to organize events and participate in a leadership group that met regularly. They called me “Socrates” because of my penchant for difficult words, complex thoughts and declarations aimed at impressing the teachers. I politely competed with a small group of bright friends who consistently had good grades, each with different strengths (mine was writing). My closest friends were Eduardo Abbate, Carlos Guaia, Adrian Garzon and Carlos Seijo (whom I had met in kindergarden). It was important for me to keep up with them and perform at their level.

The reward was to be in the “Honors’ Wall” located at the reception hall of our school, where everyone who entered could see who the best students were. I was the only serious competitive tennis player until the last two years in school, when others started playing tournaments thanks to Guillermo Vilas’s ascent. I had developed a strong sense of individuality through my relatives and a burning ambition tested on the tennis court. In my club, if you were a winner, they praised you; otherwise, you did not practically exist.

I tried different hats during high school, testing my preferences during extra-curricular activities: sports journalism (I wrote about soccer matches), organizing the first conference ever held by my class featuring a well-known Federal judge, producing short plays to be performed at national holidays, mentoring younger students and publishing a school-wide newsletter with other class leaders.

In contrast, I remember twice reaching the limit of my emotional control and punching two bullies in the face, something completely out of character for a class leader. These guys were the loudest and the biggest, so felt they could push everyone around, anytime. I knew my turn would come, so I had decided I would have none of it. When they attempted to bully me, I hit them in the face before they could react. They were stunned and enraged, but I had timed my response to be just a few steps from a teacher or when we were entering the classroom. Everyone noticed my stunt and it enhanced my status and my self-perception. To my peers, I became an unknown quantity, someone difficult to pigeonhole, stereotype or clearly define - and I liked it that way.

My school offered different ways to practice social engagement as Catholic students. I participated in weekend visits to hospitals organized by prayer groups to comfort bed-ridden children. I stopped doing it when my tennis tournaments’ schedule intensified, but I remember feeling useful when a badly burned little girl would smile and appreciated our weekly visits. I also remember their humble parents and relatives trapped in the somber atmosphere of the public hospital, where seeing uniformed boys visiting them lightened their mood.

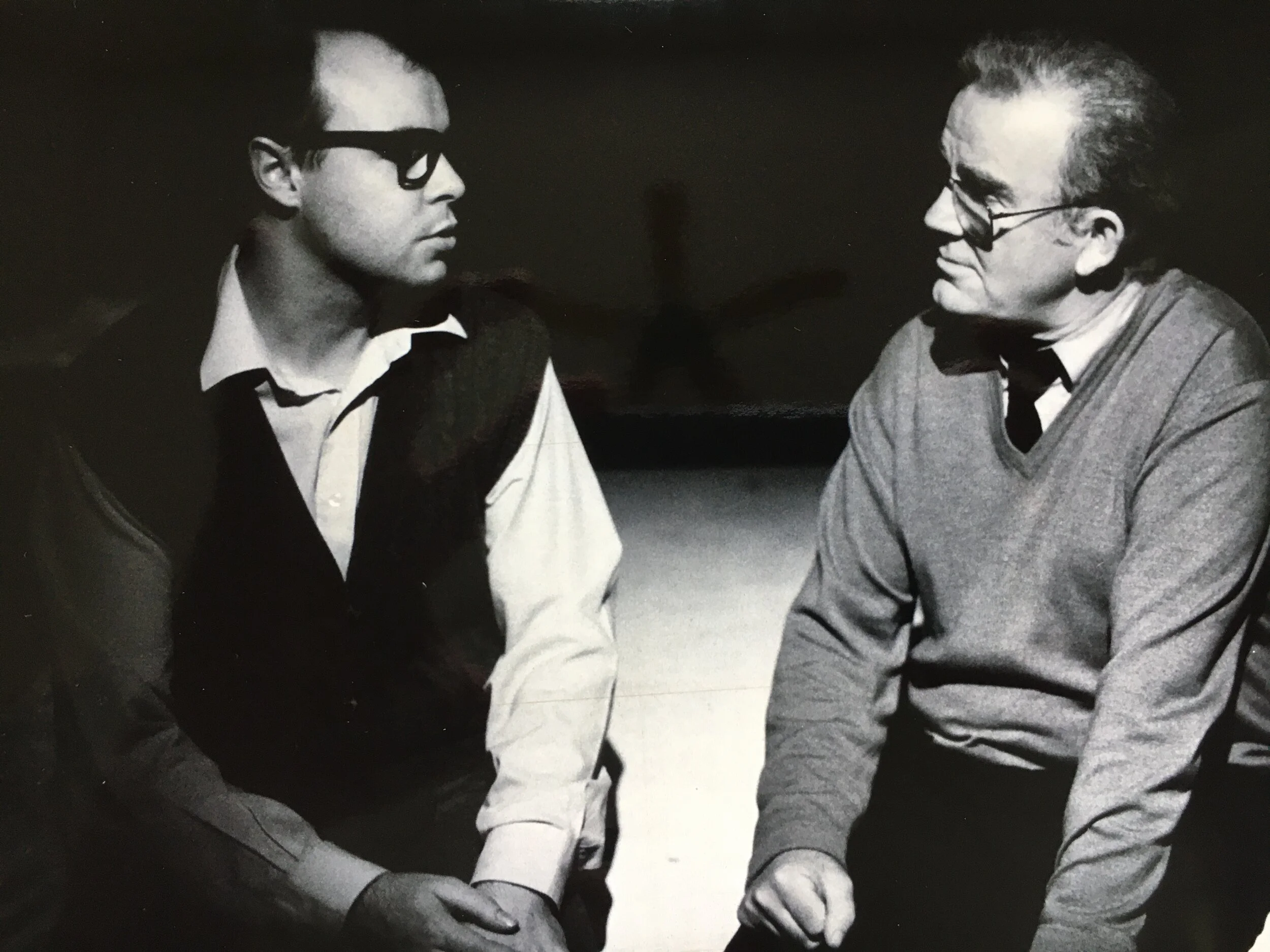

argentine writer jorge luis borges with professor jesus lopez

Jesus Lopez, my Literature professor, had a big influence on me when I was 17. He introduced me to the pioneering writers belonging to the "Latin American Boom" in the '70's (Julio Cortazar, Ernesto Sabato, Mario Benedetti, Mario Vargas Llosa, Juan Rulfo, Alejo Carpentier, Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel Garcia Marquez). Their stories and the worlds they took me into, as well as the existential choices of their characters, enthralled me.

In 1974, Argentina was submerged in the last chapter of Dictator Juan Domingo Peron’s life after he had returned from his exile in Spain, aided by the rise of the Montoneros revolutionary movement. They were determined to gain power to push forward their agenda for social justice but Peron humiliated them publicly as if they were unruly punks. Because of his blatant betrayal, they became a clandestine militia and the kidnappings, bombings and killings accelerated. When Peron died, his widow Isabel took over as president alongside a coterie of grifters. Other extremist armed groups flared up in some of the provinces, which paved the way for a military coup on March 25, 1976.

As a student at a private Catholic school where the son of a past military president had been my peer, I would have not had access to progressive ideas and socialist authors if I hadn't met Professor Lopez. An interesting characteristic of the French Brothers was to keep a wise balance between the demands of conservative, right-wing parents and other Humanist perspectives they thought we should understand. Some of the younger Brothers exposed us to anti-fascist ideas that could help us understand our role in society better, before they were shuttled to far out posts. Professor Lopez made me realize I was living inside a mayonnaise jar and that the world was much different than I imagined it. Literature was his medium; his objective was for us to become better thinkers.

"Un Alma Pura (A Pure Soul)" - a short story by Carlos Fuentes (Mexican writer and diplomat, 1928-2012) from his book "Cantar de Ciegos (Song of the Blind)” inspired me to become a writer. It’s a homecoming story where the female narrator cynically unveils the result of her savage manipulation. It opens with a quote by Raymond Radiguet: "But the unconscious maneuvers of a pure soul are even more peculiar than the schemes of vice,” an essential clue that lured me into unpacking it. With his incisive questioning, Jesus Lopez stretched my understanding of the literary craft and simultaneously questioned my prejudices. He taught me how to analyze a story, find its theme and meaning, and understand its social and historical context. I fell in love with the work of the writer and its capacity to create worlds where we can explore ideas and ways of being.

My parents rewarded my graduation from high school with a family trip to Europe. Because they had purchased the airfare to travel at a time convenient for my parent’s work schedule, I did not attend the graduation ceremony with my peers. We went to England (we got a private tour of Wimbledon, despite it was close, thanks to a kind groundskeeper who took pity on us and liked Guillermo Vilas), France (where I fell in love with my relatives and promised myself to learn French to talk to them) and Spain (we arrived to Madrid the night General Franco died, toured the South for a week and returned to watch the crowning of King Juan Carlos).

I could have chosen to study several professions (perhaps even Medicine earlier), but I was determined to become a writer - the only one among 90 students in my class, to the disappointment of my family and teachers. A vocational test determined I was interested in the knowledge provided by Medicine but not so much in dealing with patients. A counselor recommended I study Medicine anyway, since otherwise I would have no work options while the country’s economy was imploding. Stubborn as I am, I entered Literature with honors, only to face reality at the time: the military dictatorship was determined to clean up the country of intellectuals.

Thou Shall Not Think

Despite the paralyzing effects of a permanent state of siege and constant economic chaos, my parents encouraged my brother Robert and me to expand our minds continuously. Early on, we knew that we would inherit our dreams, not a fortune.

The cleansing of the Argentine society intensified under the military Junta that assumed power in March of 1976, whose clandestine counterinsurgency system effectively eliminated thousands opponents without legal due process (the numbers range between ten thousand and thirty thousand people, depending on the source).

I was eighteen years old. I had rejected studying Medicine (the science intimidated me) and inopportunely enrolled in Literature, just when it had become the hunting ground for military death squads, along with Sociology. Naively, I dared to dream in Technicolor while the Junta's National Reorganization Process demanded unconditional allegiance to their black-and-white version of Hell: either you marched in lockstep or you would be "transferred" to the bottom of the ocean.

The Armed Forces systematically rammed down our throats their fascist and fundamentalist dogma while committing mind-blowing atrocities, intending to infuse our young souls with "purpose" and "absolute certainty" in the infamous tradition of the Nazis and the Spanish Inquisition. They were the “right side” and exterminated any opponents.

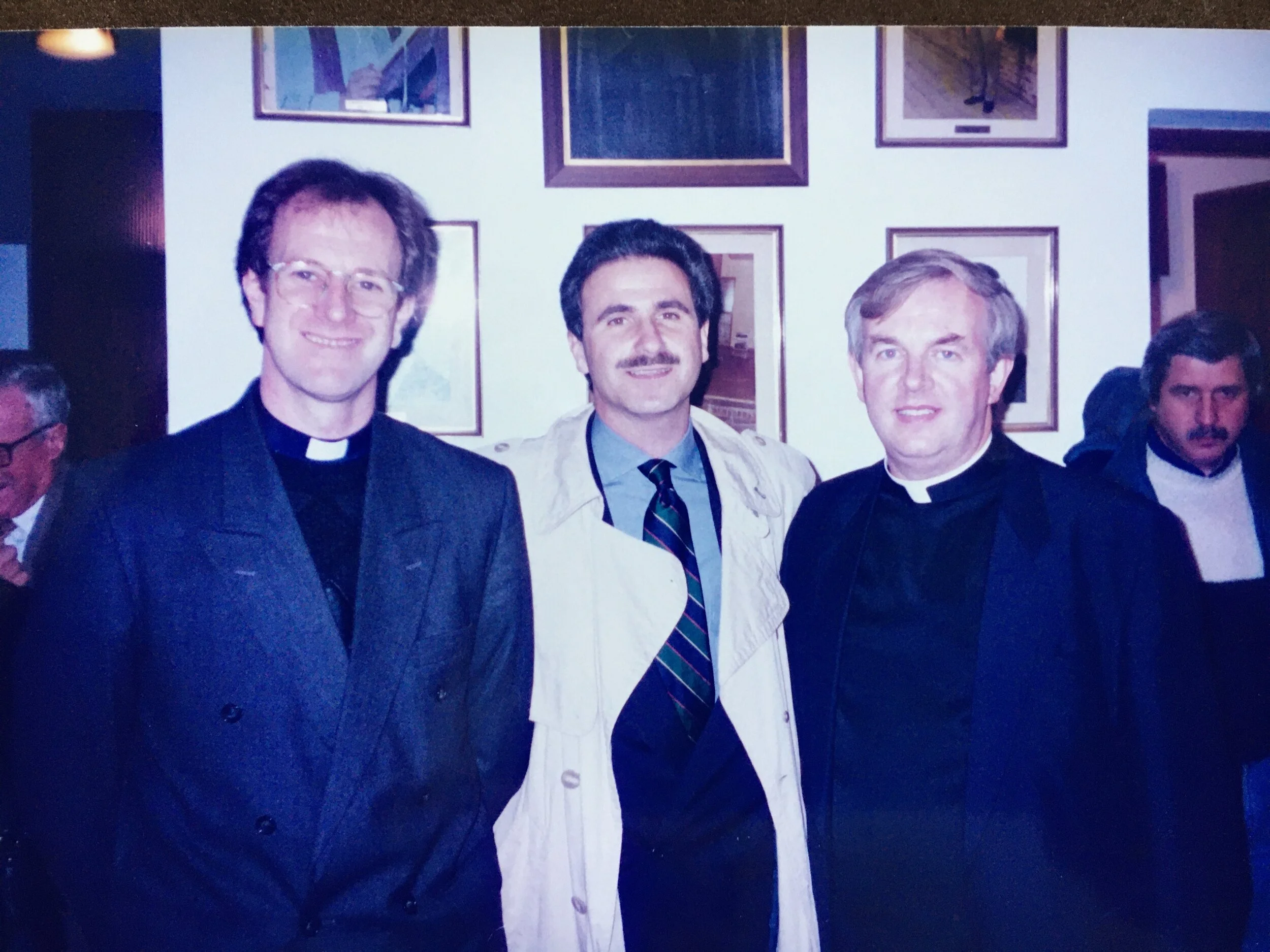

The Massacre at St. Patrick’s Church

On Sunday, July 4, 1976, at 8:15 am, I stood behind a police barricade, staring at the parochial house of St. Patrick's church. A few moments earlier, the bodies of Pallottine priests Alfie Kelly, Alfredo Leaden, and Eduardo Dufau, and of students Emilio Barletti and Salvador Barbeito were lying face down in a pool of blood in their living room. They had been tortured for several hours and executed from behind with more than sixty-five bullets.

The massacre at St. Patrick’s is the most violent crime against members of the Argentine Catholic Church in its 400-year history, perpetrated by a Navy death squad composed by six members of the Armed Forces who operated at the Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics (ESMA), the most notorious prison camp during the Junta's regime.

Father Alfie Kelly had been my spiritual advisor for a few months. The right wing, ultra-conservative Catholic sect Opus Dei had set foot in my high school before I graduated and they intentionally tried to recruit me to attend mass at their residence near my home. Their recruiting style was targeted: one evening, as I stepped out of a bus, there was a well-dressed young man waiting who started asking me questions. He seemed to know quite a few things about me and mentioned someone at my school. He invited me to visit their residence a block away. I went to a few meetings and gradually realized that the organization’s agenda was diametrically opposed to the openness and vibrancy I had experienced at St. Patrick’s all my life.

Father Kelly reluctantly accepted to counsel me because, as I later learned, he was under attack from a group of neighbors who considered his preaching style offensive. They denounced him as a political threat to the local bishop (who was a police informant) and gathered signatures petitioning his removal. One politically influential neighbor connected to the dictatorship and extreme-right death squads was probably responsibly for arranging his killing. Alfie, true to himself and his mission, gave blistering homilies based on the Gospels, not politics. He reminded parishioners of their commitments as Catholics, which irritated a swath of the neighbors whose comfort depended on their ties to the dictatorship.

I once went to see him at the parish carrying my tennis racquets. Working-class youngsters surrounded him, several of whom probably didn’t know what tennis was. None of them seemed impressed by my weird-looking Wilson T-2000s, made of metal. Their stares and respectful silence clashed with my naïve enthusiasm as I tried to explain how anyone could learn to play tennis. One of them asked what their price was. I told him the amount in dollars. He asked how much that was in pesos. There was dead silence, and another guy said, “That’s three times the monthly salary of a factory worker.” I had no response for that, but I felt no judgement from anyone, despite the ocean of inequity between us. It was one of the many hard lessons on privilege I received through life.

A few days before he was assassinated, Father Kelly made me aware of how my education had prepared me to lead and the responsibility it implied. He sensed I was destined for high achievement, management and having power over others. If that would happen, I had to ensure I would use my privilege and opportunities to teach, uplift, inspire and facilitate the advancement of others. Then, he unexpectedly told me we would not meet again because there would be big changes in the parish. He deftly brushed aside my anxious questions (“Are they sending you somewhere else?”) and before our last goodbye he made me promise that, if I ever had power over others, I would not exploit them. “Don’t use people,” he said.

Many years later, as I read his personal diaries for the theatre play I wrote about the massacre, I realized that Alfie knew he would be assassinated and who had denounced him as a “Communist,” a lie equivalent to a death sentence. In his diary, Alfie hoped his death would not be in vain, that it would serve a higher purpose. He had offered himself as a martyr to the Virgin Mary in writing back in 1963.

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Adolfo Perez Esquivel declared that the massacre was a thoroughly planned, well-coordinated military operation designed to weaken the scruples of the Catholic Church and to frighten the increasingly rebellious intellectual middle-class.

As I watched two ambulances take their bodies to the morgue, I swore that one day I would do something to honor the five martyrs' memory. Two decades would go by, but I finally did.

My Life as a University Student

As a Literature student, unidentified agents in civilian clothes patted me down for weapons and searched for explosives every single day when entering university. Initially, the classes were full. I was one of approximately one thousand students who had passed the entrance exams. Some of the professors were conservative politically but were luminaries in their field. Within a couple of months, I noticed the classes getting smaller; attendance was falling dramatically. I would find myself with three students alone in a large auditorium and a bored professor.

There were rumors that the Armed Forces kidnapped or killed some of the students. The goons were in plain clothes, driving in unmarked cars (the notorious green Ford Falcons) picking up citizens to take them to concentration camps. Other times you would see a small army entering a house and taking away its occupants. Cadavers appeared on the streets everywhere around the country. Bombings were frequent and a couple of times our entire 14-story building was evacuated in the middle of the night due to phone threats.

My mother knew I felt lost and arranged a meeting with writer Fryda Schultz de Mantovani, who collaborated at the prestigious Editorial Sur with writers Victoria Ocampo and Jorge Luis Borges. Miss Ocampo funded my mother’s scientific research of leukemia through her foundation. She met with me, asked me to read a short story about a conversation I had with Father Alfie Kelly (an epiphany he had shared with me from when he was five years old), and afterwards told me: “You will be a writer, Carlos.” The power of words to create destiny is enormous. Those giving advice must always be mindful of their words. Mrs. Mantovani specialized in children’s literature. She once wrote: “Childhood is when almost all men are poets. And those who continue to be is because they’ve kept in their eyes and spirit the capacity for awe. To look back at childhood is the sign, or rather the alert that a civilization has already suffered a long time with its drunkenness of mechanical progress and its long imprisonment within rationalist barriers.” Her encouragement resonated with me and inspired me to live poetically.

In a moment of despair, I went back to the Opus Dei’s residence for a confession. The Spanish priest in charge confessed me in his bedroom, which did not interpret as a red flag. I had to kneel while he sat besides his desk. At the end of my confession, he told me that he could only absolve me if I renounced my relationship with the martyrs at St. Patrick’s (I have no idea how he knew I had been with them). “Those priests were the devil,” he said. I felt the same unstoppable anger I felt when I punched the two bullies in high school. I stood up and said, “That’s never going to happen.” He insisted and said something about my soul going to Hell but I told him I didn’t care. He must have sensed my blood boiling, so he backed down and finally absolved me. I left in a hurry and we both knew I would never come back.

After the massacre at St. Patrick's, my father decided I should quit Literature and look for something else. The Argentine “Dirty War” was in full force. I was lost. I started weekly therapy sessions, without which I would not be who I am today. My father connected me with a friendly yet fascist Judge with whom he played tennis. I worked as a clerk in his Criminal Court for a year at the central Law Courts (Tribunales) in Buenos Aires, where every day I compiled the dossiers of the “N.N.” (Unknown) cadavers left by death squads around the city, among other crime and death cases. When I was sent to the police with requests for Habeas Corpus, they never answered. Remarkably, the Judge and his assistants claimed to know nothing about the military repression, until his right-hand officer told us one day that colleagues had seen people shackled to the basement walls at a military regiment within the city.“ The military would never do that,” was the Judge’s comment.

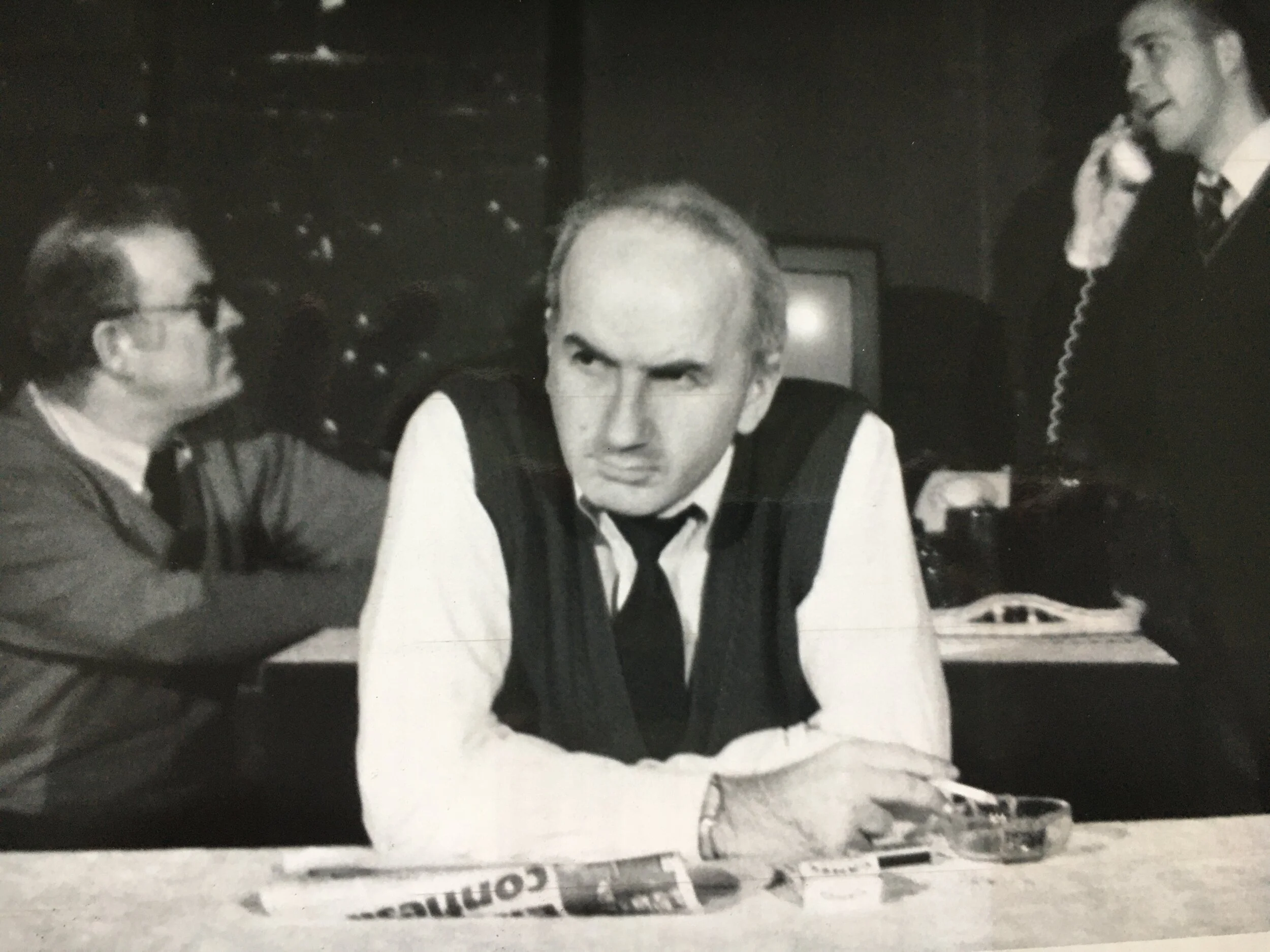

with writer omar ramos

The stories I witnessed during my time at the Law Courts could fill volumes. There were the Judge’s idiosyncrasies and cowardice, the defense lawyers’ flamboyancy, the unequal treatment of prisoners, the cast of characters at the tribunal ( one of them was an “actor” who had never been more than an extra), the “panels” to judge pornography (I had to bring them dozens of croissants), the policemen drunk on wine mid-morning who had never shot a gun, and the coffee servings every hour for six hours, until we begged them to bring us only two teas per day.

Fortunately, I met someone with whom I could compare notes about the madness surrounding us, Omar Ramos, who worked in my tribunal. We both went to Catholic schools and found out that his father and my mother had studied Chemistry together at the university. Omar was a perennial law student and loved to write. He invited me to many gatherings and parties and introduced me to wonderful women, as a masterful matchmaker. We shared books and worked on his stories, he corrected mine, and we went to movies and plays. I admired his persistence; it was certain that Omar would one day become a published author. In the past 20 years, he published “Lugares Violentos,” “El Cielo y el Infierno,” “Sangre en las botas,” followed by “La Elegida,” “El Ultimo Pecado,” “Recordando a Julio,” “El dolor de la ausencia,” “La Ruptura,” as well as poems and collected short stories. They have common themes: power, abuse, religion, the quest of the writer and the decisions an individual must make to survive, to preserve a sense of meaning. Omar is a kindred spirit who has also acted on his mission as a storyteller from the intellectual, Catholic middle-class and witnessed with astonishment the degradation provoked by Fascism in Argentine society.

Having decided that the Law was not for me (I dreaded the paperwork, the delays and the double standards I witnessed), I chose to study Medicine (my therapist persuaded me with illustrated books on the history of Medicine that featured more art than science, a very clever ruse on his part). After studying the entire summer, I passed the entrance exam with very high marks. I was one of the top 1,000 among 13,000 applicants.

It was very tough for me to concentrate during my Medicine studies. Coming from a family of scientists with several PhDs and international recognition, the expectations were high. Some of my professors knew my parents socially and professionally. I only liked the topics were art helped me relate to the science, such as cytology, psychology and pathology, because I could draw what I saw. Much later, I realized that I was studying with outdated books: the French Testut anatomy books could not stand up to the ones by Netter from the U.S. (Netter had created infographics in slim volumes, versus the thousands of descriptions and convoluted, small print drawings in the Testut).

One outstanding professor had spent time in the U.S. and taught us pathology through art. I wished everyone could be like him, he knew how to help us understand and remember. One indelible example was how he used Michelangelo's "Night" sculpture on Giuliano de Medici's tomb at the San Lorenzo Basilica in Florence to teach us about carcinomas, pointing to the tumor on the androgynous figure's left breast. He also told us about its possible meaning: although the immortal artist benefited greatly from the banking family's support, perhaps he intended to forecast their inevitable demise as they ignored the warning signs of their own destruction, unable to shed the cancer triggered by their thirst of absolute power. When I went to Florence, I went to see the sculpture. I bought a postcard and sent it to him with my deep gratitude for teaching me pathology through art in context. Seeing better, seeing more, seeing deeper, seeing differently - for life.

I studied for four years with mediocre results, went to Europe and the United States on a trip totally financed by tennis lessons I gave my friends, and when I returned, it felt as if I was watching myself struggle under water.

I dragged my feet for another year at the School Hospital, where I saw my teachers become disillusioned with the profession. Despite supporting military rule, they blamed the dictatorships for destroying the economy, education, resources, investment in science and the profession itself by placing bean counters to run hospitals rather than medically trained administrators. “We only have aspirin and iodine to cure most illnesses. The hospital employees broke the new electronic microscope because they thought it would compete with their jobs.” Their evident discouragement mirrored my own lack of enthusiasm. Life in the hospital was no match for a life of adventure in Europe and the U.S.

I’m an epicurean; I didn’t think I was made for that kind sacrifice. I envisioned a different lifestyle… As the song says: “How Ya Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm (After They've Seen Paree)?” My parents’ generation grew up understanding delayed gratification and sacrificed themselves for a spot in the professional middle class. I could delay getting a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, but I wanted to enjoy both the journey and the company.

My decision to quit was gradual. I kept teaching tennis lessons and expanding my services to more clubs with a team of collaborators. I kept writing tennis articles in several magazines. Soon, I was coaching internationally ranked players and being mentored by Enrique Pisani, a top expert on Sports Training Theory. Enrique gave me the confidence to go out in the world (he immigrated to Europe before me) and make my own way as a tennis coach. It was a Quixotic, radical decision, but it was the one pulling me forward.

Manifesto: Why I play tennis

I play because tennis teaches me to be the author of my success.

Like a marble statue, I was once a formless block with hidden potential. My skills were in a rough state, my emotions were scattered and my destiny was uncertain, yet my determination to improve hinted at undiscovered possibilities. Through tennis, I've been able to carve out the shape of my dreams, the strength of my will and develop a passionate determination to win.

I play tennis because I believe that pressure is a privilege and that if I train I can overcome any challenge. My training can take my talent and skills beyond my limitations, yet my fearless engagement with the unknown ultimately shapes my reality as a confident competitor.

Tennis is a game of opportunities. There are many factors conspiring against my best intentions to perform at my best. However, time after time I'm able to view obstacles as "teachers" and implement solutions that transform me into a versatile, creative, flexible and resourceful fighter.

Tennis is my passport to the world; it's like knowing many languages at once. The net does not divide the court: it bonds both sides and engages us players into a battle against ourselves, not each other.

The lines on the court are the great equalizers: my opponent and I know and understand the rules.

The match is just an excuse to learn the lessons we need, a stepping-stone to the best we can be. In tennis, even the fiercest opponents ultimately become friends.

Winning matters as long as it doesn't define me. I play tennis to achieve, yet I play to be fulfilled. I want my presence, energy and actions to speak out for me... always positively.

My goal is to be the best under pressure, to be a permanent example of self-control, resiliency, creativity and fairness. Tennis forces me to envision solutions two, three and even four steps ahead. A tennis match is a design; it's a struggle between imagination and implementation.

Everyone who watches me play must instantly understand that I'm not just a tennis player: I'm the conqueror of my emotions, of my goals, and a champion who's leaving a path for others to follow. I conquer them by increasing my capacity through training, by embracing challenges and by backing off the battles to recover and learn the lessons. The pulse that sustains life is that of the atom, the cell, the heart, the breathing, as well as the stress and recovery waves of a tennis match. By sustaining this pulse, I aim to be a nucleus that radiates powerful energy to reach and positively influence others.

Every time my brother Robbie and I meet, we celebrate playing tennis - as we've done through life, including before significant life events and celebrations. We are eternally grateful to our father, who wanted us to play because he thought it would be like mastering a foreign language: a tool to engage, understand, travel and grow. He was right, as tennis became the conduit for us to emigrate to the U.S. and reinvent ourselves. His investment paid off. We always tried to be there for his birthday and play at our centenary British club. We improved his game, brought him increasingly bigger and more powerful racquets so he could beat his friends and joyfully played with him until he was 89. He passed away at 93 on his birthday (June 15).

Whatever I do in life, I'll always be a tennis player. Tennis defines my worldview: an environment in which I can be engaged, inclusive, global, egalitarian, fair, passionate, curious, creative, expressive... and where "play" is the spiritual bridge with others I yet have to meet.

The lessons of winning in tennis applied to achievement in business is a powerful metaphor. I’ve been able to assist business leaders and their companies achieve both incremental and exponential results. Most of my executive clients are attracted to the peak performance approach, yet that's only the first step towards more significant endeavors, as they ultimately seek a new sense of meaning and fulfillment, and a relevant personal legacy. I want the same for myself and I’m willing to train for it.

our yearly ceremony - every june, robbie and I returned to buenos aires and played tennis with my father

Tennis may not make one a better person, but by showing much of what is best in us, it can influence positive transformations. Like legendary tennis champions, I want to be my purpose and manifest it by joining understanding to excellence in execution to hint at life's wholeness. Leaders who act like authors influence their communities and the world.

I'm privileged to have met and worked with remarkable competitors, most of whom never set out to change the world, yet by excelling at the game they showed us all that breakthrough is possible and that it's up to us overcome the obstacles blocking our path to achievement.

By the time I'm 80, I want to be known as a living example of how tennis shapes a person to be a leader. I want to be respected for my contributions to my peers and the younger generations, someone who's never content with what's given, who's always embracing the challenge to go "beyond personal best," regardless of age, condition or circumstances.

I play tennis because I can't imagine not doing it. It’s part of my identity. When I play, I feel I’m fully myself.

The Essence of Tennis

Tennis is a game of opportunities.

Tennis is a contest between two (singles) or four players (doubles) who hit a ball with racquets over an obstacle (the net) and within a rectangular surface (the court). It requires you calculate distance, identify angles, cover your territory and manage the force and speed of your shots.

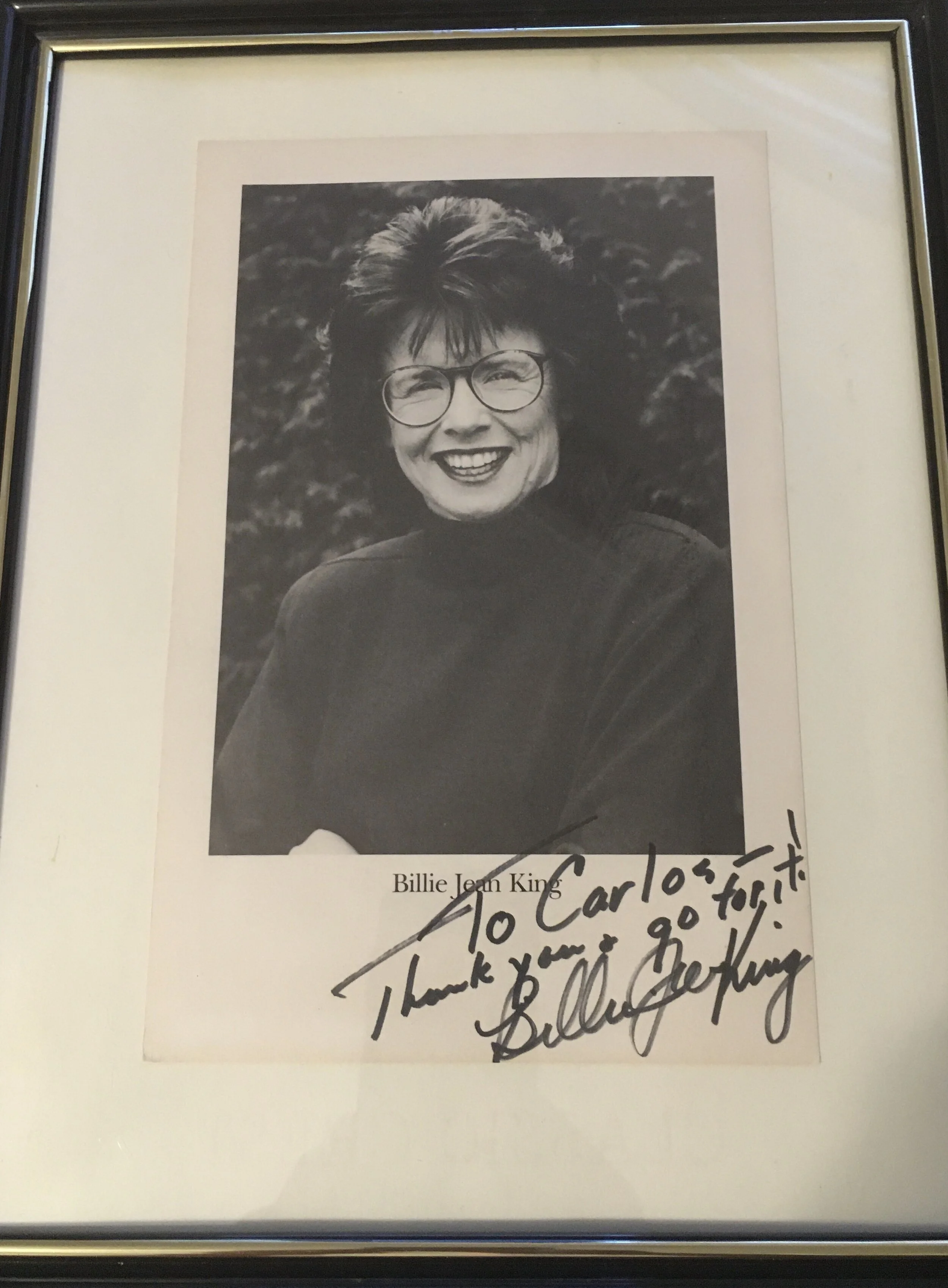

Billie Jean King has said, “Tennis is a perfect combination of violent action taking place in an atmosphere of total tranquility.”

The purpose of tennis is:

to force the opponent to make an error

to get a high ball or short ball to put away

Consistent winners in tennis...

Know the geometry of the court: you can dissect the court with angles that allow you to control the center

Adjust their position relative to the height, distance and speed of each shot

Adapt their tactics to fit their skills, their opponents' style and the score

Tennis is strength in motion. It's a game of milliseconds. Geometry, pattern recognition, reaction time and tactical choices align to execute effectively. For every shot, you must quickly calculate and dissect the angle of possible returns to be in a favorable position to win the point.

The basic tactics in tennis are Control, Direction, Depth, Spin and Speed. In theory, you could win most points by combining three dimensions: Right-Left; High-Low and Far-Near from the net. Most shots in singles land in an hourglass-shaped area aligned with the center of the court. The closer you are to the net, the better your choices to hit to seven zones outside of the hourglass-shaped area and win the point.

During the in-between-point time, four distinct stages allow players to manage their physiology and emotions precisely. Between those 16 to 25 seconds, the best competitors master essential physical and mental skills such as disengaging, relaxing, planning and visualizing, so they can play each point in a state of flow.

In Tennis, the pursuit of excellence is never-ending. The only predictable outcome is that there are no ties: you win or you lose. The match is not over until the last point, so you are always fighting to create opportunities and possibilities to solve situations.

Tennis training is both systematic and exploratory: you always have to sharpen your weapons but you must also expand your creative arsenal.

Tennis favors autonomous, versatile and independent thinkers who understand that the limits of the court and the rules allows them to stretch their intuition and judgment skills.

The net does not divide the court; it joins both sides to create a field of fairness, randomness and self-discovery.

From Becoming an Athlete to Becoming a Tennis Coach

I learned to play tennis at the Belgrano Athletic Club, two blocks away from my apartment building and nested in a neighborhood with typical British architecture and families. The British companies who built the urban railroads in Buenos Aires founded clubs alongside them for their employees and friends, featuring sports such as rugby, hockey, tennis, golf, cricket and swimming. My club has a long tennis tradition, as it hosted an international amateur tournament for many years. I had a chance to watch up-close some of the best amateur players of the 70’s until Guillermo Vilas’s international success ignited a tennis boom that accelerated professionalism. The club also has a well-regarded rugby team in the national championship and some of the female hockey players have attained World Championship and Olympic success.

The club was my second home, where professionals and international executives surrounded me. My parents were proud of being able to offer Robert and me a safe environment for skills development and socializing. We complemented our weekly English lessons at school by reading the now-defunct World Tennis Magazine, where we enjoyed Dennis van der Meer’s visual tips with Billie Jean King, Margaret Court and others. We bought the magazine subscription from Mr. Llewelyn Williams, a club member who had played Wimbledon in 1930 and was a kind supporter of our lengthy practice sessions.

Our coaches were Andres Funes, Oscar Valdivieso and Carlos Pena, who became Davis Cup Team Captain and was hopeful about my possibilities as a player. Carlos made a big impact on my development because he understood my emotional complexity and simplified tennis strategy for me. He worked on my strokes until they became weapons and taught me how to win with them. He patiently taught me tactics, week after week, and kept encouraging me, as I returned his kindness with progressively good results. I did not require much attention or desperately craved it as some of my peers, but I wanted specific keys to beat others better than me. I wasn’t as talented as them, I was the product of work and brains, and I had something to prove. Carlos shaped my game through personalized attention, overriding and surprising some tennis committee members who had discarded me into a bag of cats.

Felix Ereniu, my fitness coach, transformed me into an athlete and a winner. He was calm, thoughtful and always insightful. Felix was proud of his knowledge and although he was a tennis outsider, he was eager to learn, so he asked me to teach him the strokes so he could train me better. He took me aside one day and told me: "You are much better than you think, better than all these talented players around you. I'm going to take you as my personal project and in a few months you'll be beating most of them." His prediction became reality. His well-designed workouts made me a confident fighter and gave me a mental edge. It allowed me to try shots from every angle and spin because I knew I could get to every ball.

Soon, I caught the eye of the #1 player in the club, a tall and kind-hearted marketing executive called Alex Aron who invited me to be his doubles partner. Alex was the tennis captain at the club and competed in every open tournament in the calendar, which meant he knew many players around the country and internationally. He respected my dedication and perseverance, as well as my deadly left-handed spin serve. Getting the support from Alex and absorbing his tactical insights allowed me to believe that my training regimen would pay off.

He took a chance on me. Other top players would ask him "Why him?" and Alex just looked at me and replied: "You'll see... just wait and see." I learned a lot by playing at a high level in a very short time. Alex put to the test in competition the physical and mental capacity that Felix was building. Carlos Pena kept refining and challenging me weekly, keeping me focus on building matches one point at a time.

Gradually, I started reaching the semifinals and finals of open tournaments, winning a handful by the time I left high school and joined the better club teams (we finished second in juniors, nationally). Winning my first tournament was certainly the highlight of my young life, especially because my father decided to come and watch the final (till then, I had always traveled and played alone).

I had become an athlete. I knew how it felt to go beyond limitations and put together a win. All it took was Felix, Alex and Carlos genuinely believing in me for me to commit and create a path for success. Their personalized attention made a world of difference in my game and my self-esteem.

with gerry wortelboer in palma de mallorca, spain 1987

As I was being noticed for my progress, I was invited to practice and play by Gerry Wortelboer, who is considered the greatest tennis teacher in Argentina's history. He was a junior talent who got a scholarship to study in the U.S., where he profited from competing against the great players in the 60's. When he returned to Argentina, he brought with him an approach to teaching never seen before, which included video analysis, biomechanics, serve-and-volley, spins and, most importantly, humor. His influence in young players such as Guillermo Vilas and his generation was remarkable. Virtually every great player coming out of Argentina has been through his teaching in one way or the other.

We played mostly doubles with other solid players at the club. The matches were always electrifying, as you could count on Gerry making trick shots and doing the unexpected to win the point. Although I was a conscientious and hard-working player, I was socially insecure because I had been discarded as erratic, temperamental and a choker early on. Playing with Alex, Carlos and Gerry allowed me to gain confidence in my abilities and to unfold my potential. At that stage, their acceptance and compliments on my progress were more important to me than my results. They had not given up on me although I was not a star and they delighted in teaching me new ways of doing things – and I made sure I delivered. Each match with Gerry felt like a university exam. Playing in front of an audience that doubted my abilities forced me to dig deeper and concentrate harder. The difficulties of the matches minimized by his jokes, funny expressions and quick wit. I felt truly immersed in the competition and enjoyed it as a unique creative experience. It felt safe, for at the end there will be no judgement, no drama, just more laughter and support.

When I decided to become a tennis teaching pro, he generously offered his assistance and mentorship. My brother Robert learned a lot by watching how he led by example. For a couple of years, we rented a private court he had built in a residential neighborhood to give private lessons, which helped our business significantly. Not many teaching pros had access to such opportunity.

argentina davis cup team 1984: gerry wortelboer (captain), horacio de la pena, martin jaite, roberto arguello, juan carlos belfonte (trainer) and jose luis clerc

When Gerry became Argentine Davis Cup Captain in 1984, he called us to assist him during the USA-Argentina tie. The team featured Jose Luis Clerc, Martin Jaite, Horacio de la Peña and Roberto Argüello. My role was a tough one: I had to imitate John McEnroe's serve for two straight weeks. Every morning, I thought my arm would fall off. It was exhilarating to be part of the elite team and learn from Gerry’s insights. His trust was a badge of honor for us.

As a coach, I’ve focused on following my tennis mentors’ example, on being a catalyst for transformation and tangible results. The unexpected validation has come from those who understood the process and did the work: "You did not just made me a champion, you changed my life." In those moments, I always remember with gratitude those who helped me overcome mediocrity, self-doubt and shame through kindness, understanding, encouragement and ultimately friendship.

Becoming a Tennis Coach - and Suffering the Consequences

My friend Gustavo Raitzin was my first paying tennis student. It felt good to stay connected to tennis while I was trying to sort out my life at the university. Once my young professional friends learned I was teaching, they promptly formed a private group and we started to meet on weekends.

In 1981, I traveled around Europe and the U.S. for two months with money I had saved from teaching lessons for two years. During that trip, I enjoyed my solitude, the connections I made at Youth Hostels, trains and restaurants, and visiting all the great museums and landmarks of London, Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Munich, Vienna, Salzburg, Venice, Milan, Rome, Florence, Barcelona and Madrid. Then I went to New York, where I soaked in the city and its art as well. Those two months were the happiest time in my young life, where I understood what pulled at the strings of my heart.

My last stop was Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where I became certified by Dennis Van der Meer, the legendary "teachers' pro." That experience changed my life. Watching Van der Meer marshal his operation with entrepreneurial zeal was a revelation for me. As a tennis evangelist, he was outstanding at creating massive energy around him and was able to make tennis look as exciting as a riding a rollercoaster. He saw something in me.

Dennis was a South African immigrant who came to America with a racquet and a smile. He figured out a better way to teach tennis and became famous coaching Billie Jean King and Margaret Court for their "Battle of the Sexes" against Bobby Riggs. He is not just a unique tennis pro; he is a brand and an ambassador. Although he had lost a fortune during the oil embargo, he recovered and built a global organization. I wanted to follow in his footsteps, as I was certain I could learn a lot about self-realization from him.